‘We do not know one-thousandth of one percent of what nature has revealed to us’ — Albert Einstein

Gazing east at dawn or west at dusk, it’s hard to be blind to the vast colour palette that nature has splashed around the sky.

The magnificent hues of sunsets or the roiling darks of oncoming thunderstorms make you realise you only need look to nature to find workable colour schemes.

If you are filled with awe when you see colours in the sky in natural proportions, it satisfies a primal aesthetic predisposition hard-wired into your brain. You’ll probably be similarly satisfied when you see it painted in the same proportions on a wall at home.

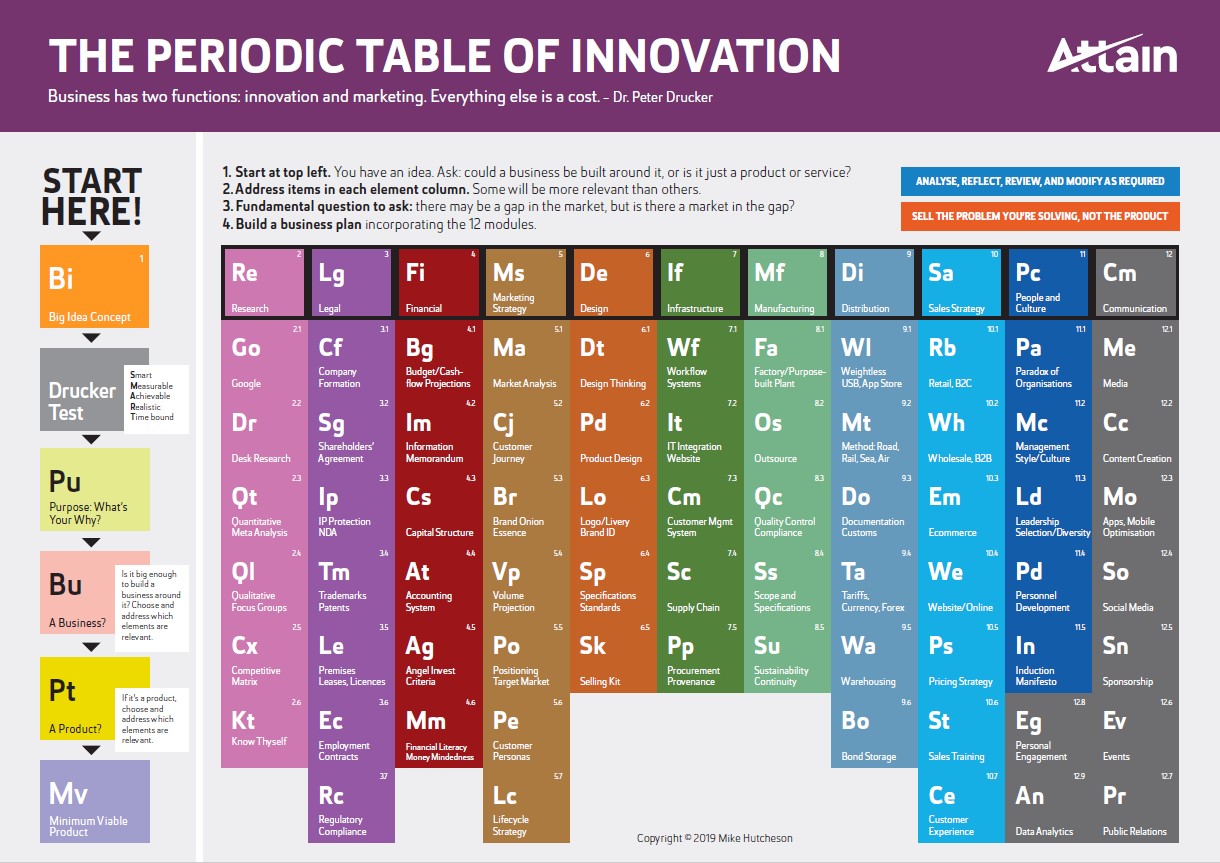

But it’s not just the principles of colour coordination that nature teaches us. The natural world is a catalyst for all kinds of human innovation. After all, if a principle has worked and survived for thousands of years in the wild, why shouldn’t we be able to make it work for us in our everyday lives?

Looking to nature for inspiration allows us to see how other life forms have been able to solve problems through evolution or adaptation. In fact, bionics is a field of science that is all about converting systems from the natural world into modern technological devices.

And we still have a long way to go. In terms of the mechanisms we have been able to utilise, it’s estimated there is only a 10% crossover between nature and technology.

Nevertheless, examples are all around us. The development of dirt-and-water-repellent paint was influenced by the observation that virtually nothing will stick to the surface of a lotus leaf. In engineering, the hulls of boats have been designed to emulate the skin of dolphins. Plant seeds have taught us about aerodynamics and burrs sticking to a hiker’s clothing led to the invention of velcro. Seeing a moggy’s eyes shining in the dark led to a road worker inventing ‘cat’s eye’ road markers. Natural camouflage in the animal kingdom has become a model for army uniforms. Ultrasound techniques have been refined by studying the way bats use reflected sound waves. Observing the sticking power of tree frogs and their complex, hexagonal-patterned toe pads has helped engineers improve the wet weather road holding of tyres.

Observation of natural phenomena and subsequent adaptation to common use is almost as old as recorded time. While nobody knows who invented spectacles, Seneca, the Roman playwright, is supposed to have read “all the books in Rome” by peering through a glass globe filled with water. A thousand years later, monks laid segments of glass spheres on books to magnify the letters. They called them “reading stones”. Long before, in the dim, distant past, someone must have picked up a piece of bulging, transparent crystal, looked through it, and discovered that it made things look larger.

Later, Venetian craftsmen, who had learned how to produce glass for reading stones, fixed lenses into wood or horn frames to enable both eyes to see the magnified images.

And here’s another item of useless nature trivia for you; they were called lenses because they are shaped like the seeds of a lentil.

You may think it’s an old wive’s tale, but it’s actually true that eating carrots may help you see better. While the effect may be marginal, the vitamin A contained in carrots feeds the chemicals that form part of the complex structure of the eye.

Another pathway to discovery or invention comes by making connections and understanding that everything in the cosmos is in some way related.

As Carl Sagan wrote, “If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first create the universe”.

We all came from stardust. We know that every atom of our bodies and everything around us is made up of detritus left over from the Big Bang. Iron is in stars we see in the sky just as it is in the soil beneath our feet. It’s in the food we eat and in our bloodstreams.

At a basic level we’re really nothing more than an organised pile of protoplasmic chemicals.

Nothing really stands completely apart. When we try to make connections between things we can open our minds to a flood of ideas as our imaginations make leaps to fill the gaps. We need to constantly force ourselves to look for how things might be related in some way, because our brains are naturally better at seeing how things differ.

Forcing relationships between apparently disparate things is a fruitful creative technique. For instance it could involve randomly opening a book, magazine or a thesaurus and asking how your problem is like something you randomly pick. Could it be like a fridge, a plant, a figure of speech, a building or a kangaroo? It matters little if it stretches your imagination. If you try hard enough you’ll eventually find a common connection.

And that’s the point. Sometimes you just need to look around you, or out the window, to see how the natural world behaves and find a linkage that will inspire you.

“To develop a complete mind: study the science of art; study the art of science. Learn how to see. Realise that everything connects to everything else.” — Leonardo da Vinci