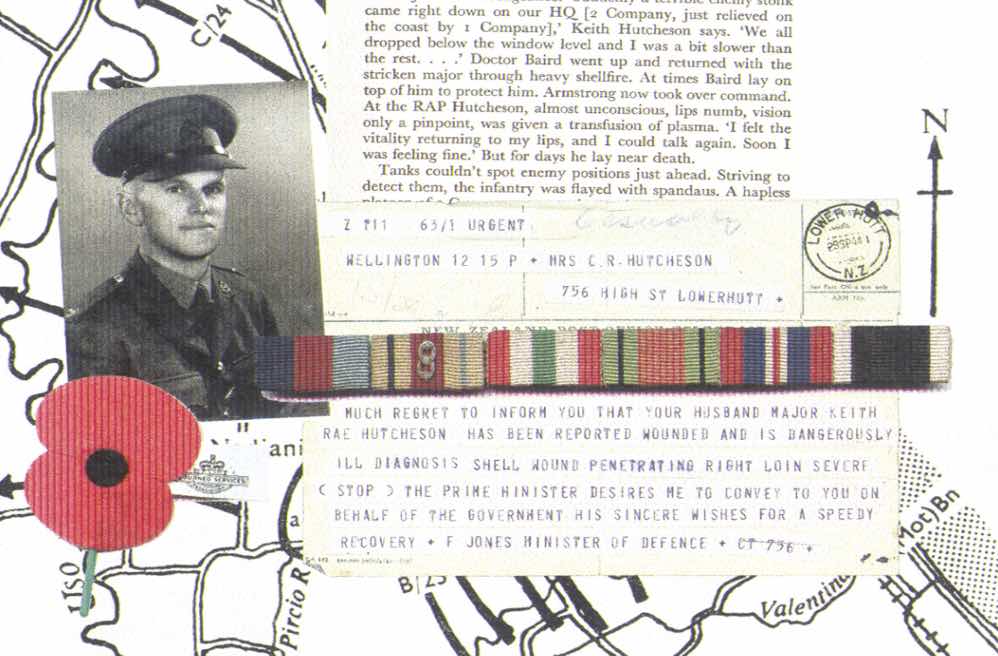

A longer version of this was originally published in The Independent Business Weekly in 2002. In these strange and uncertain times I felt it appropriate on Anzac Day 2020 to remember that our nation, and indeed our world, has been through even more uncertain times. We shouldn’t forget the sacrifices and tribulations of citizen soldiers like my father, whose lives were forever changed in a global conflict. He was severly wounded in 1944 and died in 1956, his wounds remaining unhealed, almost to the end. I only learned of what happened to him after reading his Battalion’s history. He never spoke of it and I was too young to ask. I don’t even remember him very well, but I do remember his casual clothes were khaki shorts and shirts. The shirts had epaulettes.

The Telegram my mother received to tell her her husband had been wounded.

All stories have a beginning, a middle and an end. I can write the middle and ending of this one, the beginning was written before I was born.

It is part war-story, part defining moment and part new-media miracle. Although the story began in the autumn of 1944 — it only came to life in 2001, courtesy of the Internet.

By all accounts the night of September 24, 1944 was dank and foggy in the Adriatic coastal region of Northern Italy.

Between Ravenna and Rimini, dozens of sluggish and unremarkable watercourses have cut deep, muddy trenches through the alluvial silt of the Po Valley. Rio Fontanaccia is one of them. Really little more than shallow stream, it lies a few kilometres north of Rimini, now among the more popular seaside resorts of Europe. Rimini marks the end of Via Emilia, once an ancient Roman road.

2000 year old Tiberius Bridge, Rimini. The end of Via Emilia

That night the stretch of Rio Fontanaccia from the railway-line to the sea formed the start point for 22nd New Zealand Battalion — of which my father was a major, commanding 2 Company — in a renewed assault on The Gothic Line. He and his two brothers had enlisted the day war was declared. He had just graduated from university and was sent for officer training to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. He had an MA in French and English. After leaving Sandhurst he rejoined his unit in Syria then fought throughout the 8th Army’s North African Campaign; Tobruk, El Alamein and finally on to Italy.

After the fall of Rome on June 4, 1944 the Germans had retired to the defensive Gothic Line in what Churchill called “the soft underbelly of Europe.” It comprised a heavily fortified belt of Panzer turret gun emplacements and minefields, some 16 km deep, across the Italian Peninsula extending from south of La Spezia in the west, meeting the Adriatic Sea between Pesaro and Cattolica.

Panzer turret above Rimini. Part of the web of German defence right across the Italian peninsula.

Although the Gothic Line offensive has been historically overshadowed by the D-Day invasion of Normandy in June of that year, it was one of the biggest battles fought during the entire North African or Italian campaigns, with more munitions being used and more artillery rounds fired than at Monte Cassino or El Alamein. It was one of the crucial battles of the entire war, launched with the aim of destroying the German Army in Italy and bringing the Allies into the Balkans before the Red Army arrived.

Unfortunately for the future of Yugoslavia, a combination of fierce German resistance and less than ideal cooperation within the Allied leadership enabled the Wermacht to slow the Allied advance during the winter of ‘44/’45, allowing the Russians to make it to the Balkans first.

The battle is well documented, particularly in the Official History of 22nd Battalion, written by Jim Henderson and published in the late 1950’s.

It must have echoed the words of Siegfried Sassoon in ‘Memoirs of an Infantry Officer.’ “And now, once again, we could hear along the horizon that blundering doom which bludgeoned armies into material for military histories.”

The fighting that night started after 8pm with an artillery barrage; “Sixth Brigade attacked on the left, moving up fast through the carnage wreaked by the crushing barrage, but over on the coast 22 Battalion ran into some serious trouble in its last night of this action. Expecting the main attack would come up the coast, the enemy laid the weight of his artillery on this area…a dismal business for the 22nd. Shells cracked and whined over the start line…No Turcomen these, but paratroopers and Panzer Grenadiers on the job with a vengeance.

Wermacht paratroopers manning a 10cm Nebelwerfer mortar

Suddenly a terrible enemy ‘stonk’ (mortar) came right down on our HQ… Keith Hutcheson says. ‘We all dropped below the window level and I was a bit slower than the rest …’ Doctor Baird went up and returned with the stricken major through heavy shellfire. At times Baird lay on top of him to protect him. Armstrong now took over command. At the RAP, Hutcheson, almost unconscious, lips numb, vision only a pinpoint, was given a transfusion of plasma. ‘I felt the vitality returning to my lips, and I could talk again. Soon I was feeling fine.’ But for days he lay near death.”

That was my father’s last day as a well man.

Now we come to the middle bit.

I had been prompted to read the history again after seeing Steven Spielberg’s movie “Saving Private Ryan”, a story about citizen-soldiers doing brave things in terrible times. My brother, Tim, read it too and rang me to say that from the maps and details in the book he reckoned the location of the building in which our father was wounded could be identified to within a few hundred metres.

Tim’s comment intrigued me enough to search the Internet to see if any maps showing Rio Fontanaccia appeared on-line. They did. As did an article written for the local newspaper on the liberation of Rimini. It was in Italian of course, headlined “Liberarono Rimini …Dallo storico Amedeo Montemaggi ” It gave the liberation date; “21 Settembre 1944..”

I could decipher the words sufficiently to know the topic and September 21 was three days before my father was wounded. A quick scroll through the article showed ‘neo zelandezi’ enough times to keep me riveted until the 2nd to last paragraph, which I absorbed somewhere in the pit of my stomach.

“Alla fine il maggiore Hutcheson si accampa con I suoi a 200 metri dalla fossa Turchetta.”

Page from Chiamani Citta – Commemorating the liberation of the city. Major Hutcheson is mentioned in the second to last paragraph.

Seeing one’s own father’s name in an obscure Italian provincial newspaper, more than half a century on, has a way of focusing the mind.

I won’t bore you with attempts made to track down the source but, courtesy of an Italian friend, I made contact with Signor Amedeo Montemaggi, who had written the article to commemorate the liberation of the city. He is an historian and has written a number of books about the Gothic Line battles.

We had a marvelous e-mail correspondence over the next couple of months. He was even able to tell me who was shooting at the 22nd Battalion. He wrote, “I think I can tell you that the Turkmenians of the 303 Regt. (Lt.Col.Christiani) were of the1st Bn. (Capt. Franke). They yielded to your father’s attack so the German commander of the 76th Armoured Corps (Gen. Herr) had to support them with the parachutists of the 1st Bn. of the 1st Para Regt.”

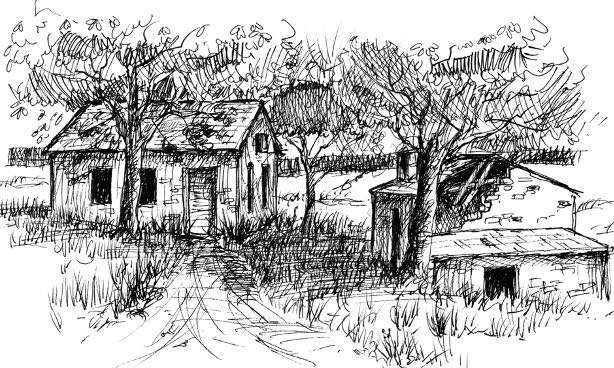

Then he sent a note with some photographs. “Taking advantage of the sunny afternoon I made a little photo-recce on the road Porto Palos, that links Rimini to Bellaria along the axis of the 2nd Coy of 22nd Bn. I found that the mouth of Fossa Turchetta is covered…that the mouth of stream (Rio) Fontanaccia is still open…I tell you this little detail just to let you know that the south bank of Fontanaccia in the sector between the coast and the railway is still as it was when your father was here, with the same brushwood and two small buildings looking very old.”

“…two small buildings looking very old.”

If one of these buildings was the site of 2 Company’s HQ on the night of September 24, 1944, it was probably pockmarked with shrapnel fragments from the mortar shell that wounded my father. I still have a piece of shrapnel from that shell — removed from his back shortly before he died. I carried it with me when I visited Rimini in 2001.

Sig. Montemaggi offered to take us to Rio Fontanaccia. It helped me figure out how to end the story. Before I finish however, let me tell you a little about Amedeo Montemaggi. He was one of the nicest men I’d ever had the pleasure to meet. He and his equally delightful wife Edda, were inseparable. He was loquacious and had the air of a slightly distracted academic.

A former journalist and teacher, he was an acknowledged expert on the Gothic Line, he’d written 12 books on the subject and has been consulted by Canadian, German and Greek military authorities. A leading light in the city, he was very much his own man, having offended both the Fascists and Communists at various stages of his career.

Though no doubt not the first, we were the only New Zealanders he knew of to come to the notice of city authorities while visiting the old battlegrounds. He arranged for us to meet the Mayor in the hall in the Town square. The square is very near the place where Julius Caesar made his famous ‘crossing the Rubicon’ speech.

Julius Caesar crossing the Rubicon

Despite the fact that our troops flattened the place during the war, we were made very welcome. Rimini has a scale and a feel with which we felt very comfortable — as well as some great restaurants and local wines.

But I digress.

Amedeo didn’t drive, Edda ferried him everywhere — I got the distinct impression that he absent-mindedly forgot his driver’s license at some time in the distant past and never felt the need to go and look for it.

We arrived in Rimini on the afternoon of June 26. Later that evening Tim surprised us by turning up unexpectedly at the hotel, fortunately he knew our travel plans. I hadn’t heard from him for some weeks when he was travelling in Central America.

The morning of June 27 dawned hot and clear — the deep blue sky glistened like highly polished steel and seemed to hum with heat. Amedeo and Edda met us at our hotel. Armed with photocopied pages of the ‘Official History of the 22nd Battalion’, our little expedition set out to retrace the advance of 2 Company during the last 3 days of Major Hutcheson’s war.

We squeezed in to our rented Opel Vectra, and drove north past the Grand Hotel, featured in Fredrico Fellini’s movie, ‘Amarcord’ which looked back on the Rimini of his boyhood. It transpires that Fellini was a ‘schoolfellow’ of Amedeo’s, albeit a few years ahead.

Grand Hotel, Rimini

But I’m digressing again.

The first obstacle confronting the 22nd Battalion was the Marrechia River. Jim Henderson described the crossing in ‘The Official History’ …

“Spandaus (heavy machine-guns) had stopped any of Hutcheson’s daylight patrols from testing the river and because of this 2 Company would have a miserable crossing…… unfortunately another bomb had blasted a crater in the riverbed …. ‘As the company forded the river in the pitch dark of a cloudy evening every man must have had the experience of plunging into a hole four feet deep,’ Hutcheson recalls. ‘With great difficulty I raised both arms and managed to keep dry my map board and walky-talky wireless’…but in 1 Company’s case all went very well indeed……a detour which under cover of the northern stopbank, took it back into position alongside Hutcheson’s sopping men, who somehow managed to flounder through their unexplored part of the river…Then, side by side, the two companies would advance, attacking over a mile to a watercourse called the Fossa Turchetta.”

This is where Amedeo’s article, written more than 50 years later, placed my father on the night of 21 September.

Rimini rather reminded us of Mount Maunganui, or Surfers Paradise without the glitzy tower blocks. Hotels and apartments line both sides of the road along kilometre after kilometre of beach. Enzo Ferrari had his villa here. The white sand is now peppered with thousands of multi coloured beach umbrellas along almost its entire length.

But in wartime the beach-front was a sinister and threatening maze. The Official History continues….

“Houses thickly dotted the land ahead and gave good cover to the enemy machine-gunners and riflemen waiting to meet the advance. …… To the right, nearer the coast, Hutcheson’s force would clash with well-equipped troops from 303 Regiment and 162 Turcoman Infantry Division, who would make the best use of fortified villas, minefields, and fortifications which had been intended to smash any invasion from the sea.”

At Scolo Brancona, baking in the sun, we found it hard to visualise the action of 1944. Behind us the hum of traffic, ahead the laughter of children, as a warm breeze wafted in from the Adriatic.

“Hutcheson saw six enemy running along the beach, set after them with a couple of comrades, landed up by a big gun emplacement and bagged fifteen Turcomen cowering in a nearby trench. The Russians obligingly pointed to a camouflaged dugout, where a solitary German under-officer was added to the bag.”

About 10am battle was joined once again, 2 and 3 Companies, with tanks, starting off up the coast towards the small seaside resort called Viserba and the canal almost a mile away. Just nine hours later, the Chiefs of Staff of (The German) Tenth Army (Major-General Fritz Wentzell) and of Army Group C (Lieutenant-General Roettiger) held this telephone conversation:

Army Group: ‘I don’t understand what is going on to your left.’

10 Army: ‘That’s right … 303 Turcoman Regiment was there.’

Army Group: ‘But isn’t the line at Viserba?’

10 Army: ‘It was. A strong enemy patrol with tanks broke through at Viserba …’

22nd Battalion, with 19 Armoured Regiment’s tanks, was responsible for this part of the chat and for scattering 303 Turcoman Regiment, in the words of the Germans, ‘to the four winds’.”

Finally, we came to the stretch of Rio Fontanaccia which was the start-point for 22ndBattalion the night our father was wounded. Miraculously it is still very much as it was during the war. The river, really little more than a wide and shallow ditch, is the boundary between two local counties and the bureaucratic complications of having to comply with two sets of building ordinances seems to have deterred development close to either bank of the river.

Amedeo had previously identified two old and derelict buildings, one of which he thought may have been 22 Battalion HQ, mortared by the Germans that night.

In the end we couldn’t be sure, but it didn’t matter, we knew we had come to within a few metres of the place we were seeking — as far as our father had come. It was now a peaceful scene with corn growing high on the far bank, from where, years before, the Panzer Grenadiers would have fired on the Kiwis.

Insects buzzed, birds chirped happily in trees that had grown since those days, heedless of the attack of September 24, 1944.

The roof has collapsed on the smaller of the two buildings, doors and windows are missing or bricked up. Damage to the walls of the larger could have been caused by shell-fire, or indiscriminate use of a hammer, it is impossible to say. But we knew we were near. We could feel it.

Larger of the two buildings is still as it was in 1944. Thanks to Google Earth 2020.

There was also a poignant irony in the shallowness of Rio Fontanaccia. You see, although his wounds never healed almost to the end, it wasn’t so much damage to his body that killed my father, it was damage to his mind. He took his own life, leaving no note or explanation. He was found drowned, lying face down in a shallow ditch. Somehow a circle was closed.

He had no epitaph and was buried in unconsecrated ground, but if there were words to go on his grave I would like them to be these. They are the closing lines of “All Quiet on The Western Front” by Erich-Maria Remarque.

“He had fallen forward and lay on the earth as though sleeping. Turning him over one saw that he could not have suffered long; his face had an expression of calm, as though almost glad the end had come.”

For the Fallen

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning,

We will remember them.

Laurence Binyon