Entrepreneurship is like the Karmasutra, reading about it is not the same as doing it.

In Harvard Business Review, August 7, 2020, Professors Ashish Bhatia and Natalia Levina asked the question; Can Entrepreneurship Be Taught in a classroom?” To paraphrase — their answer was a cautious; ‘Maybe in some circumstances’. But in my experience a qualified ‘maybe’ is misleading.

While plenty of universities offer entrepreneurship programmes of different hues and views, the big problem they all have to overcome is the lingering doubt, in most peoples’ minds, as to whether it can be taught at all.

Entrepreneurship isn’t a subject — it’s a state of mind. It’s about taking a risk, it’s about holding your nose and jumping. Or when, as a child, you learned how to ride a bike — you took a risk and held your breath as you hopped on and wobbled off, a frisson of excitement coursing through your veins when you finally felt Mum or Dad let go of your bike seat. You can’t teach that in a classroom.

Entrepreneurship is like the Karmasutra, reading about it is not the same as doing it.

There are plenty of high profile entrepreneurs who never went to business school or dropped out of university before graduating . Steve Jobs and Bill Gates being two. They both created new futures that hadn’t been imagined. They didn’t follow best practice or accepted rules, they broke them. That’s what entrepreneurship is — not following a typical business school process of constructing abstract analytical models and precise calculations.

Management guru Dr Peter Drucker famously said, The best way to predict the future is to create it.

Developing soft skills like imagination, curiosity, and counterintuitive thinking is beyond the realm of traditional business teaching.

The Bhatia and Levina study went on to identify a few top US Business schools with non-traditional methods of tackling the challenge. They can best be described as ‘learning by doing rather than learning by listening’ approaches.

The University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management has set up a medical-school-style operating theatre. Students in an auditorium watch as a professor performs surgery on a startup. A panel of entrepreneurs joins the professor in poking and prodding at these startups, demonstrating intuition and commercial insight, skills can be developed only through experience. NYU Stern’s Endless Frontier Labs, also focuses on experiential learning.

The University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business focuses on “rewiring” students to take action instead of falling into analysis paralysis. This is to encourage understanding and management of risk, by taking risks rather than avoiding them. This is the antithesis of a conventional business school approach.

However they noted that the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School continues to emphasize that business schools should teach entrepreneurship in a similar way to how other subjects are taught: by providing analytical models and tools from published academic research on new venture creation. Wharton is Donald Trump’s alma mater. Need I say more?

The current pandemic illustrates the importance of preparing entrepreneurs to face an increasingly complex, uncertain world. Teaching potential entrepreneurs to embrace uncertainty and ambiguity would be far more valuable than teaching how to conduct business as usual, albeit with entrepreneurial jargon.

Most millennials want to be entrepreneurs — something like 70% having that ambition — and many are ideally placed to be so.

They have the energy, the time and the lack of family obligations or employment commitments that enable them to make their business ideas happen. The very meaning of the word entrepreneur implies taking risks in the expectation of making a profit — the absence of the need to consider other responsibilities enables budding entrepreneurs to throw caution to the wind.

But the fact is, the average age of a start-up entrepreneur is nearer 47 than 27. Successful entrepreneurship takes courage, commitment and resilience; borne of experience and insight. This also means that by that stage in their lives entrepreneurs have had some experience before putting families and futures at risk.

Added to this, throughout my career, I’ve noted some common characteristics entrepreneurs seem to have. Traits like; determination, resilience, intelligence, independence, passion, comfort with ambiguity and uncertainty, self-confidence, self-discipline and the ability to provide or obtain financial backing through their own resourcefulness.

Budding entrepreneurs have to have the ability to solve complex problems, have a wide and varied network of colleagues and acquaintances and above all, sound people judgment.

The future is by definition imaginary, therefore it takes people with imagination to imagine it.

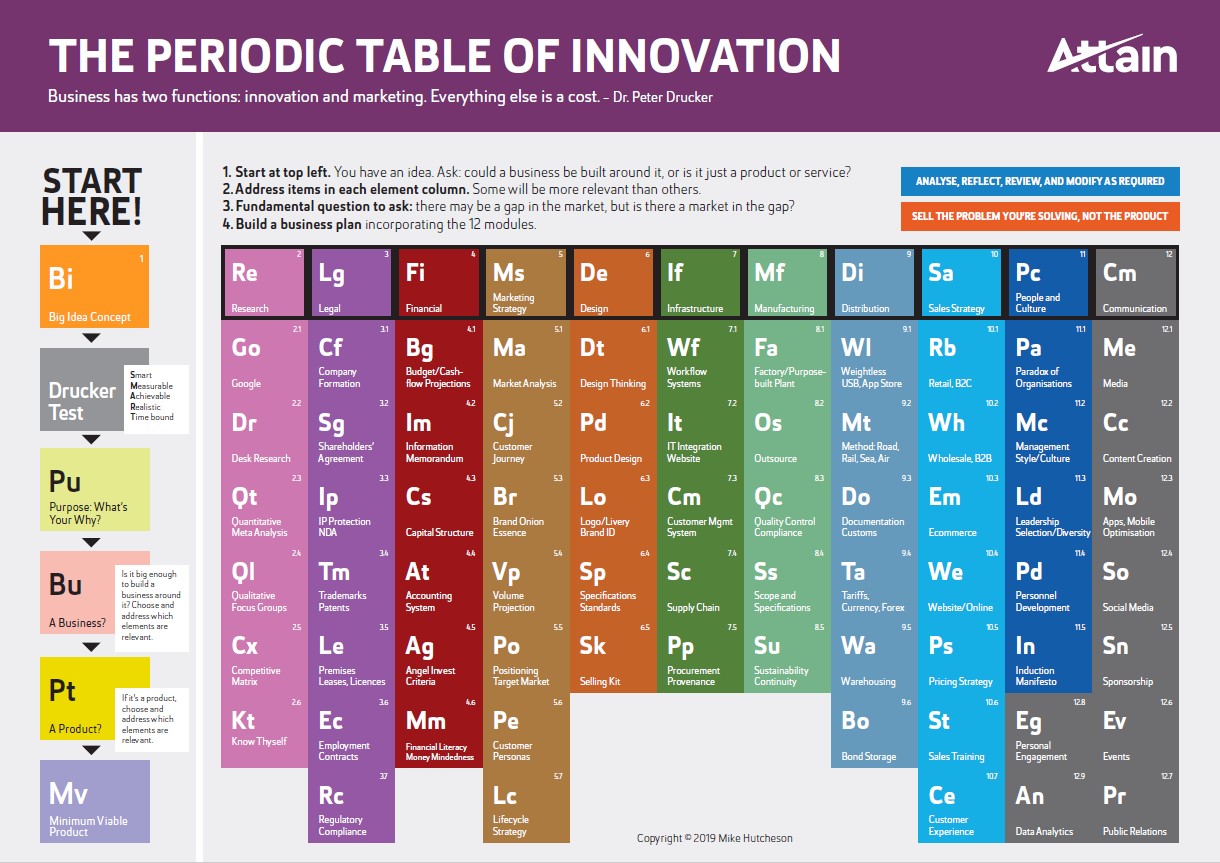

Our online Practical innovation and Entrepreneurship Course is designed for this day and age. Over a period of six weeks budding entrepreneurs can tease out and enhance these characteristics and provide a modular framework against which to develop, de-risk and validate ideas.

Find out more at www.aut.ac.nz/pracinnov.