We all remember Beethoven and his work, but no one remembers his banker. Yet there were plenty of now-forgotten people in Vienna, much wealthier than Ludwig, when he was scratching out the 9th symphony.

The point I want to make is that we pay more attention to the people who acquire wealth than we do to people who might leave something valuable behind when they’ve gone. History, of course, is kinder to those who leave a legacy.

We laud whoever is important in Queen Street, but pay scant regard to whoever is struggling at an easel or at a piano keyboard in Grey Lynn. We don’t have a framework for measuring the future worth of non-monetary endeavours.

If you don’t believe me, try using a musical score or a manuscript as collateral when seeking a bank loan! Bankers have traditionally invested in bricks and mortar — thinking they’re safe — yet look what that has done to the global economy in recent years.

According to the tenets of Jungian psychology we live in a ‘sensible’ world, with sensing (read non-intuitive) people outnumbering feeling (read intuitive) people by a ratio of almost four to one.

The problem being, if we are dominated by non-intuitives we will keep on doing what we’ve always done and continue to get what we have always got.

In the best selling, “Love’s Executioner” Irving Yalom proposes that most people don’t (or can’t) think abstract thoughts, or think creatively about what might be — they’d rather live with what they know. Spending their lives in almost constant diversion, busily avoiding and distracting themselves from confronting four bleak realities.

The first rather unpalatable notion is that they are alone — they are born alone and die alone. Hence they form committees, join clubs, conform, marry and to try and kid themselves that this is not true.

The second is the awful thought that life has no meaning. So they live their lives in a way they think they should, mimicking what they see as success, busying themselves with work, shopping, drinking, eating, having kids, playing golf, having affairs, doing crossword puzzles, getting god and religion to avoid fishing in a scary philosophical pond where they might catch the conclusion that life really is meaningless.

The third notion is that one day they are going to die. They try to avoid this anxiety by stoically bearing the ills they have, justifying it with the hope they’ll live forever in paradise or busying themselves with constant diversion and shallow pleasure seeking, before they shuffle off their mortal coils.

Finally the concept of free will freaks people out. Essentially, Yalom says, most people want structure and rules in their lives and most don’t mind being told what to do. For the majority, the fact they are responsible for themselves and have no one else to blame for their failures borders on the unbearable.

This supports why, for most people, the status quo takes precedence over discovery and spontaneity.

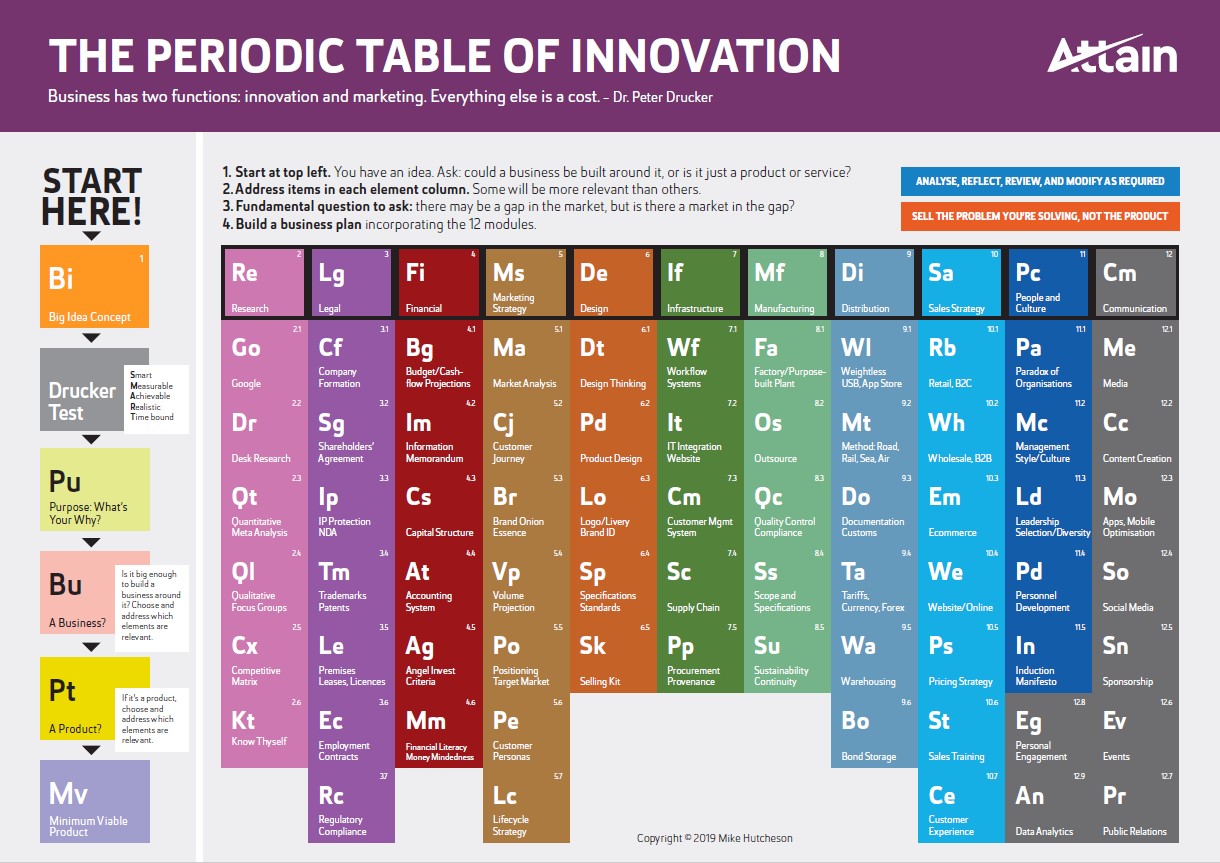

Someone once said a culture is defined by what it measures. We value short-term financial results ahead of innovation and research. Our administrators vastly outnumber our innovators. We measure inputs and outputs rather than outcomes.

For example, there are more than 28,400 registered chartered accountants throughout New Zealand, each supported by an average of 2.5 clerical staff — a total of around 70,000 souls. Yet there are fewer than 1000 people employed by advertising agencies. That means there are at least 70 times more people telling us where we’ve been than there are telling us where we should be going.

What do we learn from this? Not much apparently. The problem is compounding. From our universities there are roughly 50 times more business/accounting graduates than creative graduates. Not that I am suggesting creative training as a panacea for all business ills, just that the disproportionate ratio reflects a prevailing commercial attitude.

Which leads us to the point. How can we find a place in the sun for right-brain, intuitive people in a left-brain, non-intuitive world?

We have to accept that a career in investment banking looks a lot more attractive to an intelligent 23 year old university graduate than does a tenuous career in a creative industry.

If you are a merchant-banker you can make a fortune by sliding paper around, manipulating money or stitching together a multimillion dollar IPO, LBO, or by doing something clever with options. You don’t have to be original or invent anything new. But if you are an artist you’re lucky to get paid at all.

The only consolation for being in a creative business is that you get a chance to influence the way other people think. You may even be remembered in posterity for developing an idea or a concept that survives both you and the wealthiest financier in your street.

After all, who remembers Beethoven’s banker?