It’s taken 30 years for us to realise we can see back 13.8 billion years. But what does the next 30 years look like?

If you’re old enough to remember seeing the Berlin Wall come down and East and West Germany reuniting, Saddam Hussein’s Revolutionary Guard invading Kuwait, Jim Bolger being New Zealand’s Prime Minister and seeing Space Shuttle Discovery launching the Hubble Space Telescope into low-earth orbit, you are remembering events from 1990.

But in that year a far more world-changing event went almost unheralded. Tim Berners-Lee, an English scientist working at CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research) in Geneva, wrote a program as a “memory substitute”, to help him remember the connections between various people and projects at the lab and a multitude of other researchers around the world.

The bureaucracy at CERN was slow to recognise his efforts at finding a way to link data between the many incompatible systems within the organization, so he turned to the nascent Internet community for support.

In 1991, he made his WorldWideWeb browser and web server software available — through whatever connectivity was then in place — and posted notices to several newsgroups. The idea began to take off as more and more propeller-heads in his network around the world began setting up their own web servers. His dream of a freely accessible global information space was finally happening.

A couple of years earlier the existence of the Internet had first been noted. The initial reference was tucked away at the back of a newspaper’s financial section. It didn’t warrant a major news headline, because no-one at the time had any idea of how all-pervasive it would become.

A report in the Washington Post recorded that; “SMS Data Products Group Inc… won a $1,005,048 contract from the Air Force to supply a defense data network internet protocol router.” Whatever that meant.

It wasn’t really the year of birth of the internet concept — that had been gestating and morphing through various forms for the previous 20 or so years — but it was the first time the word “internet” had emerged into daylight.

From an arcane concept, known only to a few denizens in the rarified world of particle physics, usage of the internet grew slowly at first, then exponentially. From one originator in 1990 to about 16 million users worldwide in 1995, the number has since exploded to embrace just over 55% of the world’s population (4.2 billion) by 2020.

While it was the Internet concept that made it all possible, it was the WorldWideWeb that made it fly.

Just as TXT has created its own language in the mobile phone environment, the web has sprouted a whole new dictionary. Google, a noun that existed for only a few mathematicians before 1998, has become a ubiquitous verb in our lexicon. We no longer “look it up” we “Google it”.

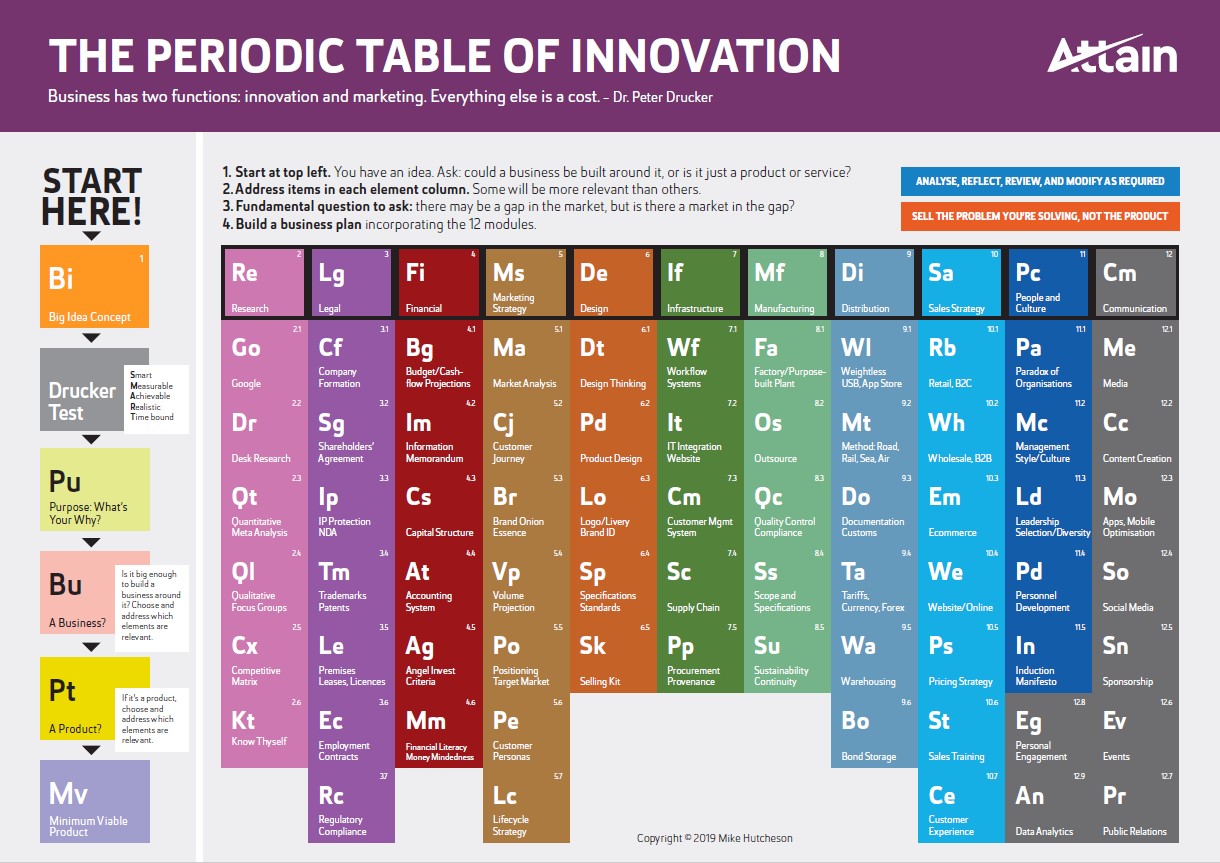

Now Google is hell-bent on transforming higher education. The company recently announced that it will be launching a selection of online professional courses, schooling candidates on how to best get work-ready for a number of careers in high demand — at a fraction of the cost of university courses. While online learning won’t replace all classroom teaching, a blended learning model involving them both is what the market is increasingly demanding.

I know this from personal experience, because it’s the call we get every day from students wanting to take our online innovation programme. https://www.aut.ac.nz/pracinnov

Putting the technology aside, I believe such remarkable growth in internet usage means two things. Firstly, globalisation is here to stay, like it or not. Secondly, and more importantly, the growth is an emphatic expression of the fundamental human need to communicate — a reflection of humanity’s search for knowledge and understanding.

That’s the point — it’s not love of technology that has driven the rapid acceptance of the Internet, but the love of learning and knowing, and that includes both receiving and transmitting.

I say this because we are not as modern as the times in which we live. In other words, although the proliferation of electronic and mechanical tools we use enables us to do stuff faster, what’s most important to us — the need to communicate — hasn’t changed much since the first conversations hundreds of thousands of years ago.

Coincidentally, on the anniversary of the internet, it’s worth noting that the latest statistics show Asia is now home to nearly 50% of all worldwide users — twice as many as in Europe and the US combined — and the Asian cohort is growing faster as a group.

Facts like these underscore that while mankind may have had its beginnings in the rift valley of Africa eons ago, in the past few thousand years it has been panel-beaten and shaped by shifting pressures of Greek, Roman, Mongolian, Middle Eastern and European hegemony into an American present. But with the cracks that are now showing in that façade I’d bet the farm on the fact that we’re heading inexorably towards an Asian future.

With around one in 5 people in the world today being Chinese and a similar number being Indian — and seeing their steady advance fueled by technology distributed through the WorldWideWeb, I think it’s a pretty safe bet.