I’ve long thought it curious that of the millions who believe they have been abducted by aliens and have returned intact, not one has managed to steal a gear knob, or souvenired a Neptunian coffee cup, or even an ionizing, warp-drive, electrozylometer from an alien spacecraft. Nothing. All they seem to come back with is a proclivity to spread conspiracy theories on social media.

Belief (bi’li:f) n. Something accepted as true, especially without proof. (Collins Concise Dictionary)

With elections looming this year in USA and New Zealand; against an international landscape of Covid-19 pandemic, where misinformation, conspiracy theories and confusion abounds, uncritical belief can be a dangerous thing. This is particularly scary in a democratic society.

The problem being that everyone’s vote has equal value regardless of any belief those votes may be based on.

It’s sobering to consider that one delusional weirdo’s vote could cancel out your indubitably intelligent, thoughtful, well researched, and altruistic support for a candidate or party who you know will benefit the nation as a whole.

And don’t for a minute think weirdos are thin on the ground. Setting aside the bizarre and divisive administration currently occupying the White House, it may interest you to know that more than six million Americans believe they have been abducted by aliens and are convinced they have been subjected to unspeakable experiments involving thought-control and anal probes.

If alien abduction were just an American thing we could laugh it off. Unfortunately such beliefs are alive and well globally. While we shouldn’t besmirch the UFO spotting community in this country by assuming they also believe they’ve been abducted by aliens, it’s worth pointing out that their logo includes a flying saucer. (see www.ufocusnz.org.nz ) Somehow underscoring an assumption that UFOs are of extra-terrestrial origin rather than errant aircraft or random atmospheric phenomena.

If we extrapolate on a pro-rata population basis, there could be around 50,000 people in this country who reckon they have been similarly kidnapped. Imagine if a closet abductee is currently standing for election and wins a seat!

I’ve long thought it curious that of the millions who believe they have been abducted by aliens and returned more or less intact, not one has managed to steal a gear knob, or souvenired a Neptunian coffee cup, or an ionizing warp-drive electrozylometer from an alien spacecraft. Nothing. All they seem to come back with is a proclivity to spread conspiracy theories on social media.

But I digress.

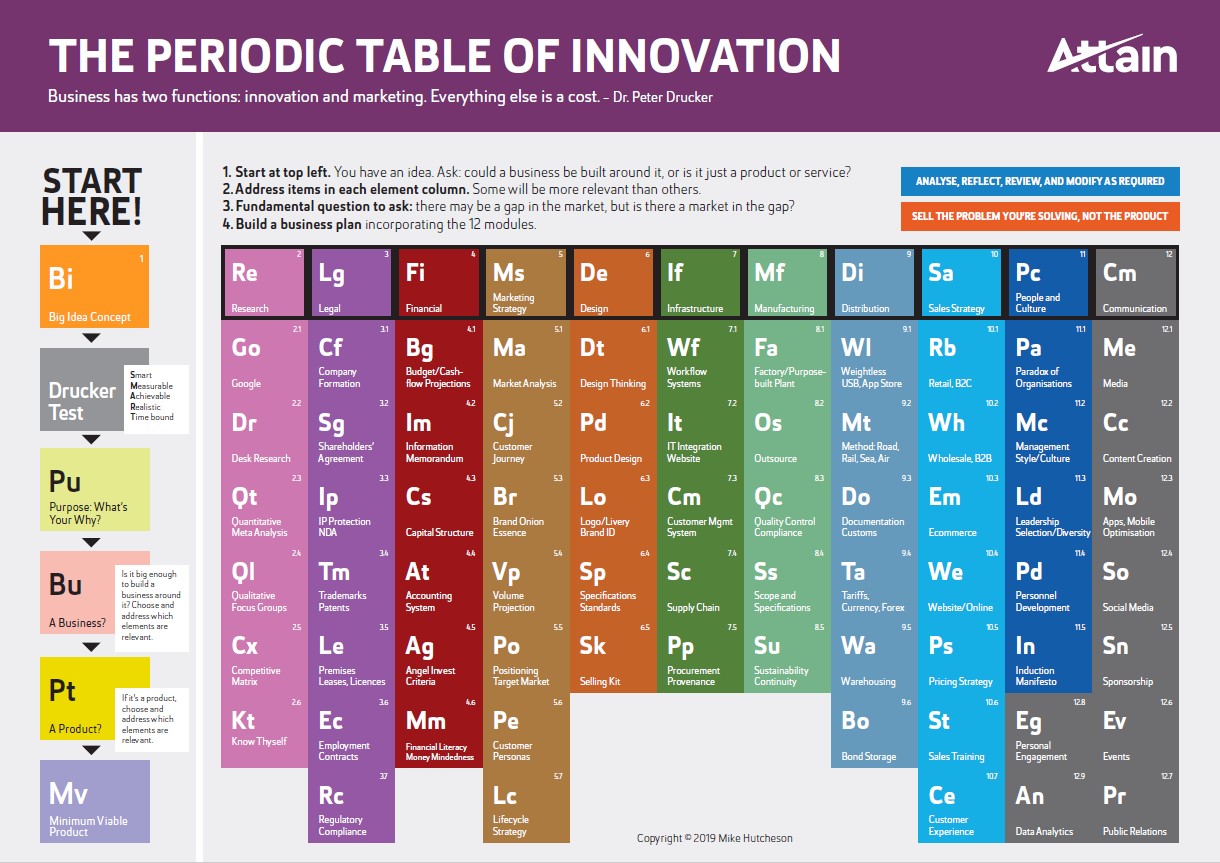

While my main task in life is to promote critical thinking and innovation, in this election year I need to give vent to distress on a wider issue — namely concern about the lack of political support for bold, innovative ideas in an MMP environment. MMP politics forces compromises and trade-offs — watering down rather than enabling bold changes.

This is why democracy fails to deliver us from mediocrity.

There’s some interesting and long-running research that helps explain this.

In the early 60s Philip Converse, a political science professor at the University of Michigan wrote a seminal paper entitled “The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics”. It summarised his research into why and how people vote. Basically he says that most people have no clear idea of why they vote the way they do and seem to have little interest in understanding issues that don’t directly affect them. Converse’s research seems to apply to all Western democracies.

He delves into and defines belief systems, concluding that most people don’t have a coherent set of values. Indeed, when questioned on why they ‘believed’ one way or the other, most of their answers were incoherent, or at best based on habitual or learned behaviour.

Converse asked a series of questions that could shed light on people’s level of political understanding and ranked their answers on a scale of 1 to 5. Level 1 indicating that people had a clear understanding of issues and Level 5 indicating arbitrary responses.

He found that only 2% based decisions on clear and coherent thinking; slightly fewer than 10% chose on rational, if ideological grounds, but about 90% voted arbitrarily, by habit, peer alignment, long term family alliances, or based on current socio-economic conditions; blaming or rewarding the incumbent party for the positive or negative situation they were in.

Electoral success hinges on the relative malleability within this group.

While there is also a politically active and, by and large, well educated group who have most contact with politicians and comment on their behaviours, they form such a small minority they have very little influence on elections. Unfortunately, because politicians tend to tap into the views of this minority as a barometer, they frequently misread the temperature of the country as a whole.

Converse concluded that rather than being a complex animal of sophisticated or even subtle shades of understanding, the electorate as a whole has few consistent political beliefs, a tendency to change opinions often and only a superficial grasp of important issues.

He was able to demonstrate that ignorance and capriciousness are more prevalent in political behaviour than intelligent decision-making.

And therein lies the danger. Imagine if, for instance, a closet abductee wins a seat and forms a political movement. With parliamentary presence, they could make us wear ‘Thought Screen Helmets’ (see http://www.stopabductions.com) to prevent the aliens from taking over our minds.

A rogue Party could try to do just that — and in an MMP environment, judging by recent events, might get support from enough fellow conspiracists to do it.

Then perhaps ‘Thought Screen Helmets’ won’t be such a bad idea.